Good examples of the most prevalent agricultural/garden pests in North America include the stink beetles (also called stink bugs, family Pentatomidae). They are so small insects but they have such a huge economic influence due to their flexibility. To understand what a stink beetle feeds on, one has to research its life cycle, the species, and the environmental conditions.

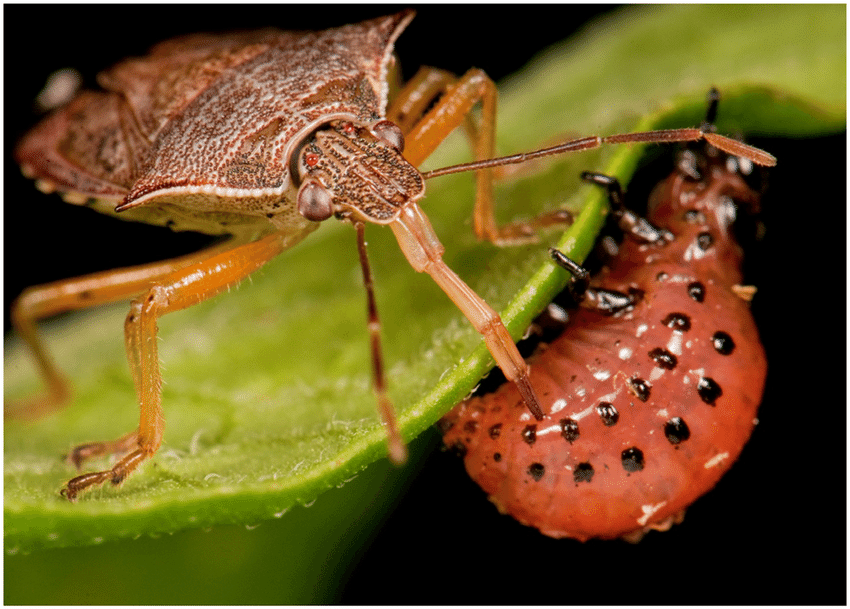

A predatory stink beetle feeding on a caterpillar using its piercing-sucking rostrum.

In 2025, the USDA and entomological extension program studies affirm that the majority of the stink beetles are herbivorous polyphagous feeders, which can feed on over 100 species of plants.

Fewer of them, such as the spined soldier bug (Podisus maculiventris), are predatory insects and offer useful pest control services.

The guide affords an in-depth examination of the stink beetle feeding, lifecycle feeding transitions, agricultural influence, and damage recognition intended to meet the needs of farmers, pest administration experts and horticultural academics searching for a study-based source of information.

Stink Beetle Diet by Type and Lifecycle

The majority of stink beetles feed on plants, fruits, and vegetables and suck fluids out of the plants with piercing-sucking mouthparts.

Their tastes change with the year and stages of life. Nymphs feed mainly on the weeds and grasses, but the adults shift their feeding to the fruits, vegetables and the field crops. A few of the species are predatory and they eat other insects.

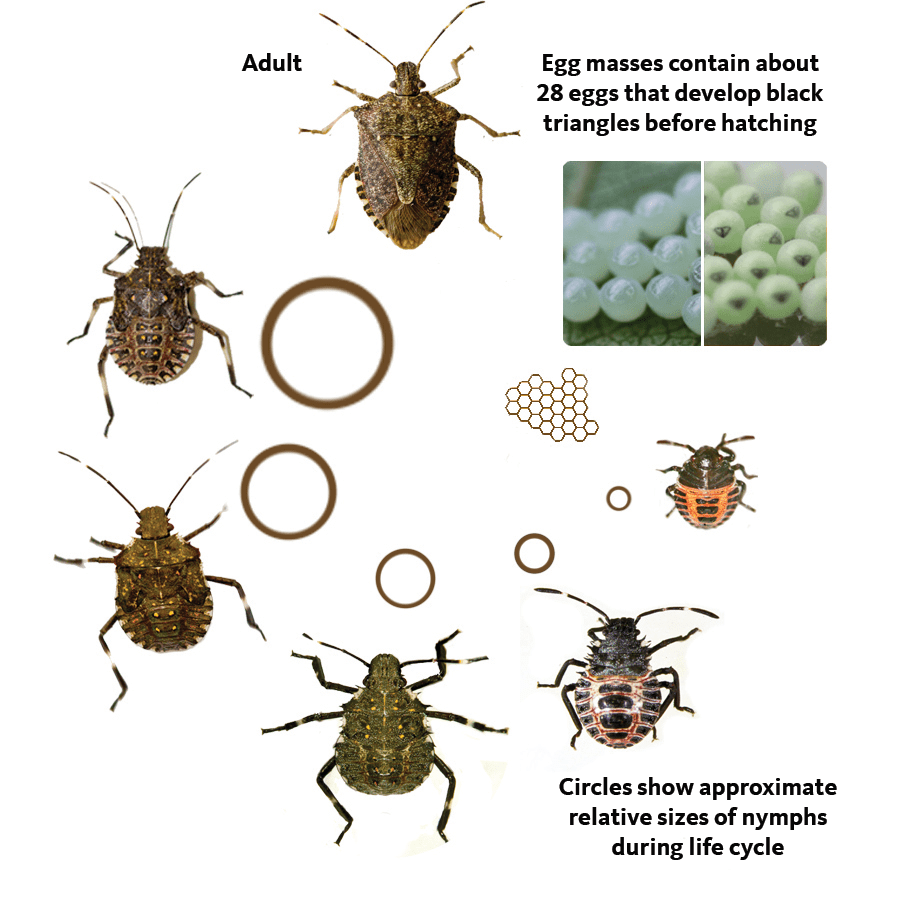

Life cycle of the brown marmorated stink beetle: from clustered eggs to five nymphal stages and finally the adult form.

Typical Feeding Patterns by Stage

| Life Stage | Primary Food Sources | Secondary Food | Seasonal Pattern |

| Nymphs (Early) | Weeds, grasses | Plant sap | Spring-early summer |

| Nymphs (Late) | Soft fruits, leaves | Developing vegetables | Mid-summer |

| Adults (Spring) | Grasses, young plants | Flower buds | May-June |

| Adults (Summer/Fall) | Fruits, vegetables, seeds | Occasional insect prey | June-October |

| Adults (Winter) | None (dormant) | – | November-March |

| Predatory Species | Insect eggs, larvae, and nymphs | Minimal plant sap (spring only) | Active year-round in warm regions |

Common Host Foods

The stink beetles are polyphagous i.e. they possess wide feeding preferences in fruits, vegetables and ornamental crops.

They can live in virtually any vegetation they can find and therefore, can be said to be one of the most stubborn pests in mixed agricultural settings.

- Fruits: apples, peaches, pears, grape vines, cherries, raspberries, apricots and figs.

- Vegetables: soybeans, tomatoes, peppers, corn, beans, cucumbers, okra, eggplants and cabbage.

- Ornaments: sunflowers, magnolia, holly, mimosa and cotton.

Food variety enables them to survive in orchards and city gardens and graze them through the growing season when foods are harvested in turn.

They are also flexible, and therefore they can overlap generations, with nymphs and adults co-existing on different crops. One adult is able to destroy five to ten fruits in a day and multi-generational infestations may destroy the output of specific geographic areas in one season.

Economic Summary

The outbreak of the brown marmorated stink bug in the Mid-Atlantic (Halyomorpha halys) alone caused over 37 million dollars worth of losses to the fruits in 2010. Losses of 10-20 million a year would be incurred by 2025 despite the improved management systems.

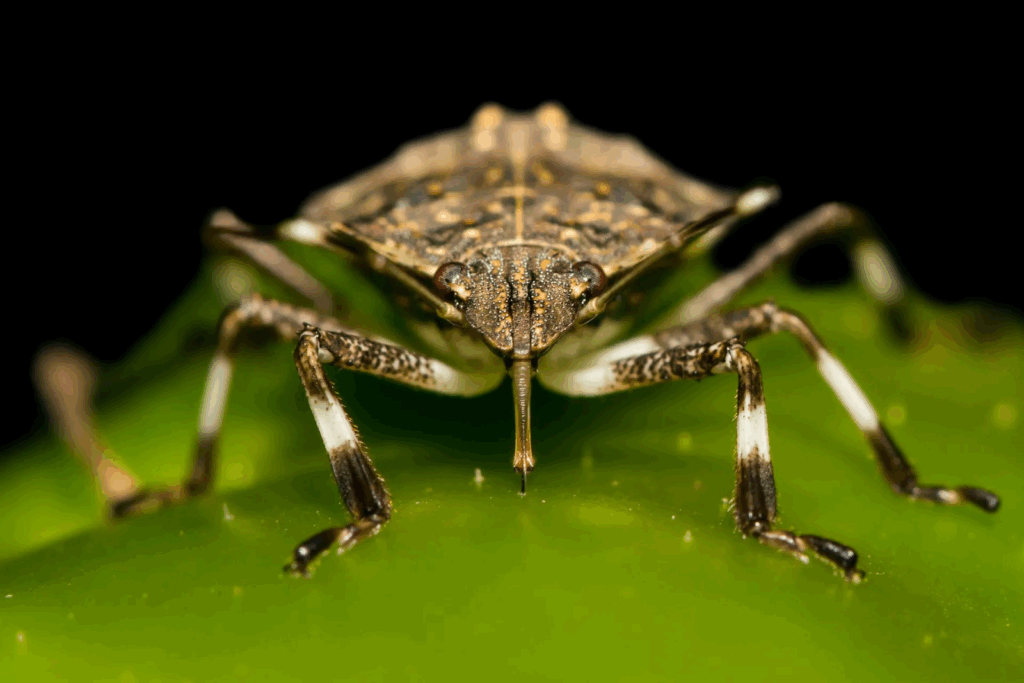

How Stink Beetles Feed – The Feeding Mechanism

Feeding organ of the stink beetles is the specialised organ (the rostrum) which is a long, jointed beak-like organ that acts as a needle and as a straw.

This sucking-piercing action enables them to perforate the exterior shell of fruits, vegetables and plant stems, unleash their digestive juices and absorb the resultant nutrient-rich liquids.

Four stylets, two mandibular and two maxillary, are found on the rostrum, which collaborate with each other to pierce tissue and create a food canal to absorb liquid food.

Stink beetles feed on a ripening fruit, causing puncture scars and bruising typical of crop damage.

Anatomy and Function

When not in use the rostrum folds down under the body. The stink beetle stretches it forward during feeding with the tip against the plant surface and the stylets piercing the epidermis.

Within seconds, saliva is injected through one canal, while a second canal simultaneously withdraws dissolved plant sap or cell fluids. The salivary glands secrete a complex mix of proteolytic and amylolytic enzymes that pre-digest plant tissue externally before ingestion.

These enzymes not only liquefy plant cells but also trigger defensive chemical responses in the host plant. This biochemical warfare damages plant tissue far beyond the initial puncture site, contributing to the characteristic spotting, necrosis, and “cat-facing” deformities seen in fruits such as peaches and tomatoes.

Feeding Process Overview

- Locate the host plant using visual and chemical cues.

- Extend the rostrum and pierce the surface using the stylets.

- Inject saliva containing digestive enzymes and mild toxins.

- Liquefy plant cells and phloem tissue externally.

- Suck the nutrient-rich sap through the food canal.

- Withdraw and move to a new feeding site, often several times per fruit.

A single adult may create 5-10 punctures per fruit per day, each one releasing enough toxin to ruin commercial value even if the wound appears minor.

Damage Pattern Created

- Entry point: Small puncture, often invisible for the first 24 hours.

- Toxin spread: Surrounding cells collapse, producing darkened or spongy tissue.

- Visible effects: Bruising, scarring, and the distinctive “cat-facing” pattern on fruit skin.

- Secondary infection: Fungal and bacterial pathogens often inhabit puncture sites.

- Economic result: Changes in appearance and texture of fruits result in downgrading or rejection in the fresh markets.

The spot is just one of the problems, the internal damage makes it less firm, less sweet and decreases the storage properties. In the processing industries, the slightest infestations may interfere with the quality of canned goods or juiced products.

Predatory Feeding Variation

More piercing-sucking beetles which use the same anatomy are predatory stink beetles like the spined soldier bug (Podisus maculiventris) and two-spotted stink bug (Perillus bioculatus).

Nevertheless, rather than extracting the sap of plants, they inject insect victims with paralytic saliva. It takes minutes for this fluid to rot the internal organs and the predator can then extract the liquefied tissues.

They are useful biological control agents due to their feeding habits that reduce the population of Colorado potato beetles, the armyworms, and other pests.

Ecological Implications

The precise mode by which stink beetles can be successful also increases their agricultural influence. They can feed in dry conditions as they can penetrate hard rinds of fruits and so outcompete most other sap-feeders.

Their flexibility coupled with polyphagous feeding is why one invasive species can inhabit numerous environments and plants.

Diet Changes Through the Lifecycle

Stink beetles go through five stages of nymphal growth before maturity and each stage has its individual dietary requirements and feeding capabilities.

This level of development defines the manner and time at which they bring the greatest agricultural destruction.

| Stage | Typical Diet | Reason for Diet | Damage Severity |

| Stage 1-2 Nymphs | Grasses, weeds, tender shoots | Mouthparts soft, low energy demand | Minimal |

| Stage 3-4 Nymphs | Leaves, flower buds, plant sap | Developing strength, higher nutritional needs | Moderate |

| Stage 5 Nymphs | Fruits, vegetables, seeds | Fully hardened mouthparts, preparing for adulthood | High |

| Adults (Spring) | Grasses, buds | Recovering from dormancy | Moderate |

| Adults (Summer/Fall) | Fruits, vegetables, grains | Peak metabolic activity | Critical |

| Adults (Winter) | None | Dormancy (diapause) | None |

The late summer is a high-feeding period when the adult insects accumulate fat reserves which will keep them alive until winter arrives. It is during this pre-winter period (September-October) that damage to the economy is greatest.

Diet by Species – Herbivorous vs. Predatory Stink Beetles

Approximately 95 percent of all known species of stink beetles are herbivorous, and they feed on plant material, whereas roughly 5 percent are predatory insects, attacking other insects. It is the knowledge of the available species that dictates the control or conservation.

| Species (Common Name) | Scientific Name (first mention) | Diet Type | Primary Foods | Economic Impact |

| Brown Marmorated Stink Bug | Halyomorpha halys | Herbivorous | Fruits, vegetables, grains | Major pest; $37M annual losses |

| Southern Green Stink Bug | Nezara viridula | Herbivorous | Soybeans, legumes, citrus | Moderate-high crop losses |

| Green Stink Bug | Acrosternum hilare | Herbivorous | Corn, beans, soy | Regional pest |

| Rough Stink Bug | Brochymena quadripustulata | Herbivorous | Seeds and legumes | Minor pest |

| Spined Soldier Bug | Podisus maculiventris | Predatory | Insect larvae, beetles | Beneficial; natural pest control |

| Two-Spotted Stink Bug | Perillus bioculatus | Predatory | Colorado potato beetle stages | Highly beneficial |

| Dusky Stink Bug | Euthyrhynchus floridanus | Predatory | Beetle and moth larvae | Beneficial, southern species |

Predatory species can save $50-$200 per season per field by suppressing destructive beetle and caterpillar populations, while herbivorous species can cause up to 40% yield loss in soybeans and 90% damage in peaches and apples.

Agricultural and Economic Impact of Feeding

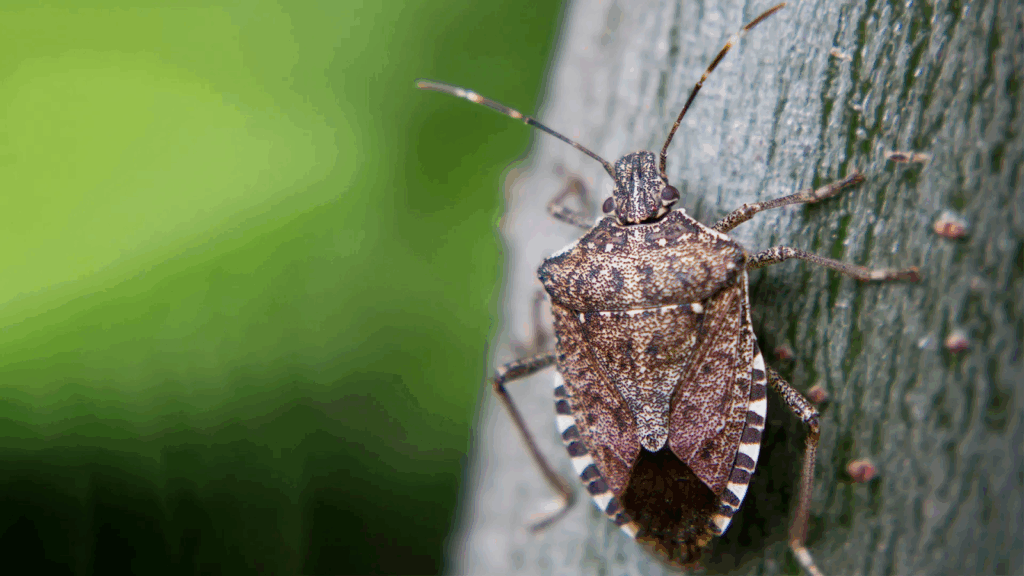

Stink beetle (brown marmorated stink bug) perched on tree bark, ready to feed.

The brown marmorated stink bug has been the most harmful species in American agriculture.

- Soybean wastes: 15-40% reduction in yield.

- Stone fruits (apples, peaches): Fruits: 30-90% of the fruits cannot be put on the market.

- Corn: 5-20 percent of the corn is damaged, and it is not normally evident until harvest.

Case Example – 100-Acre Soybean Field

The average production in a 100-acre soybean farm is approximately 50 bushels per acre, or 5,000 bushels in a 100-acre plot. The revenue is expected to be 60,000 at a price of $12 per bushel at the market price.

- Nonetheless, a 25 percent loss of yields because of infestation by the stink beetles translates to an estimated loss of income by 15,000.

As the amount paid out in monitoring and treatment goes up by an extra thousand dollars, pest management will be a profitable investment to secure the profits.

Return on control investment: 15:1

- USDA data suggest that effective management of stink beetle populations through pheromone trapping, border spraying, and biological control can reduce average national losses to under $20 million annually.

When and Where Stink Beetles Feed Most

Feeding intensity varies with temperature, season, and region. In southern states, activity begins in early spring and may continue through December, while in northern states feeding is confined to May through September.

Monthly Feeding Calendar

| Month | Feeding Status | Typical Foods | Notes |

| Jan-Mar | Dormant | None | Overwintering indoors or under debris |

| April | Minimal | Grasses, weeds | Low activity post-dormancy |

| May | Low-moderate | Flowering plants, leaves | Egg laying begins |

| June | Moderate | Early crops | Nymph populations rising |

| July-Aug | Maximum | Fruits, vegetables | Peak damage and population density |

| Sept-Oct | Intense | Late-season crops | Reserve-building before dormancy |

| Nov-Dec | Minimal → Dormant | None | Migration to overwintering sites |

Regional Feeding Periods

- South: March-December (3-4 generations annually)

- Mid-Atlantic: April-October (2-3 generations)

- North: May-September (1-2 generations)

- West: Nearly year-round in California; seasonal in the Pacific Northwest

Field studies show that 70-90% of damage occurs within the first 40 feet of field edges, a phenomenon called the “edge effect.” Early detection and border treatments are therefore critical.

A brown marmorated stink beetle displaying its piercing mouthparts; an organ that enables diet shifts from sap-feeding nymphs to fruit-piercing adults through its lifecycle.

What Stink Beetles Do NOT Eat

Another myth that has been present is that stink bugs feed on meat, wood, or household material, or indoors. And in the real sense, their mouth parts will not be able to penetrate human skin and cannot digest any non-plant foodstuffs.

| Category | Feeding Behavior | Notes |

| Humans/Pets | Cannot bite or feed | Mouthparts too weak; no disease transmission |

| Animal Meat | No feeding | Only predatory species target insects |

| Wood/Fabric | No damage | No chewing mouthparts |

| Pet Food | No consumption | Not attracted to animal protein |

| Rotten Food | Avoids decomposition | Prefers living, fresh plants |

| Indoor Behavior | Shelter only | Winter dormancy, not feeding |

People can find stink bugs in the house in winter but this does not mean that they are actively seeking food; it is merely seeking shelter. When not active, they only live on the fat that is stored within them.

Identifying Feeding Damage in Crops and Gardens

Recognising stink bug feeding damage helps distinguish it from diseases or other insect injury.

Characteristic Damage Signs

| Crop Type | Damage Indicators | Impact |

| Fruits (Apples, Peaches) | Brown puncture scars, “cat-facing” marks, internal bruising | Cosmetic rejection, rot spread |

| Soybeans | Pod deformity, shriveled seeds, “stay-green” effect | 15-40% yield loss |

| Corn | Hidden kernel shriveling, grain discoloration | Downgraded grain quality |

| Tomatoes/Peppers | Surface dimpling, discoloration, internal softening | Market rejection for fresh produce |

| Cucumbers/Beans | Misshapen pods, scarring | Reduced harvest grade |

| Ornamentals | Leaf stippling, flower discoloration | Aesthetic damage, replant cost |

The damage is normally noticeable within 3-5 days following the act of feeding and may continue within two to three weeks as bruising becomes severe and secondary infections become established.

Feeding Behaviour and Foraging Patterns

The damage is normally noticeable within 3-5 days following the act of feeding and may continue within two to three weeks as bruising becomes severe and secondary infections become established.

Stink beetles clustered on a tomato, showing their foraging pattern of group feeding that amplifies damage through repeated punctures and toxin spread.

Key Foraging Behaviours

- Visual targeting: Detect green or red plant colors and shapes.

- Olfactory detection: Sense fruit volatiles, plant stress chemicals, and aggregation pheromones.

- Aggregation: Release pheromones to attract others; leads to clustered feeding and concentrated damage.

- Daily activity: The best feeding time is between 11 AM and 4 PM when the temperatures are not more than 75-90°F.

- Temperature dependence: Activity declines below 60°F and above 95°F.

- The “edge effect” described in field studies indicates that damage near field borders can be up to three times higher than in interior rows. Monitoring these edges provides an early warning for growers.

FAQs – Quick Reference

Q: What do stink beetles eat?

A: Mostly fruits, vegetables and plants. The soybeans, apples, peaches, tomatoes, and peppers are fed on by adults, which the nymphs begin with weeds and grasses. Insects are preyed on by savage species.

Q: How do they eat?

A: They also inject digestive enzymes into a plant and suck the liquid using a rostrum. This results in cat-facing which is bruising and scarring.

Q: When do they feed most?

A: Between June and October, the busiest season is late summer and early fall.

Q: Do they feed in winter?

A: No. They enter dormancy (diapause) and live off stored fat. Indoor stink bugs are sheltering, not feeding.

Q: Are any stink bugs beneficial?

A: Yes. Predatory species like the spined soldier bug consume harmful crop pests and should be conserved.

Q: How severe is the economic damage?

A: The U.S. losses are more than 10 -20 million annually due to soybean and fruit crops.

Q: How can farmers recognize their damage?

A: Look for grouped puncture scars, bruising under skin, and delayed crop maturity (“stay-green” effect).

Conclusion From Allen Tate

The dietary habits of stink beetles shape their ecological and economic impact. While herbivorous species such as the brown marmorated stink bug threaten hundreds of plant species and millions in crop value, predatory species contribute meaningfully to natural pest control.

Understanding what stink beetles eat, when they feed, and how their lifecycle influences behavior remains the cornerstone of integrated pest management. With accurate identification, regional timing, and crop-specific monitoring, growers can balance control measures against beneficial species, minimizing losses and maintaining sustainable agricultural systems.