Understanding the Western Hemlock Tree

Western Hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla) is a coniferous tree of the Pacific Northwest, which is considered one of the most iconic trees of this region.

This is an evergreen that is known to tolerate shade remarkably, growing in dense forest understories where other conifers would not grow.

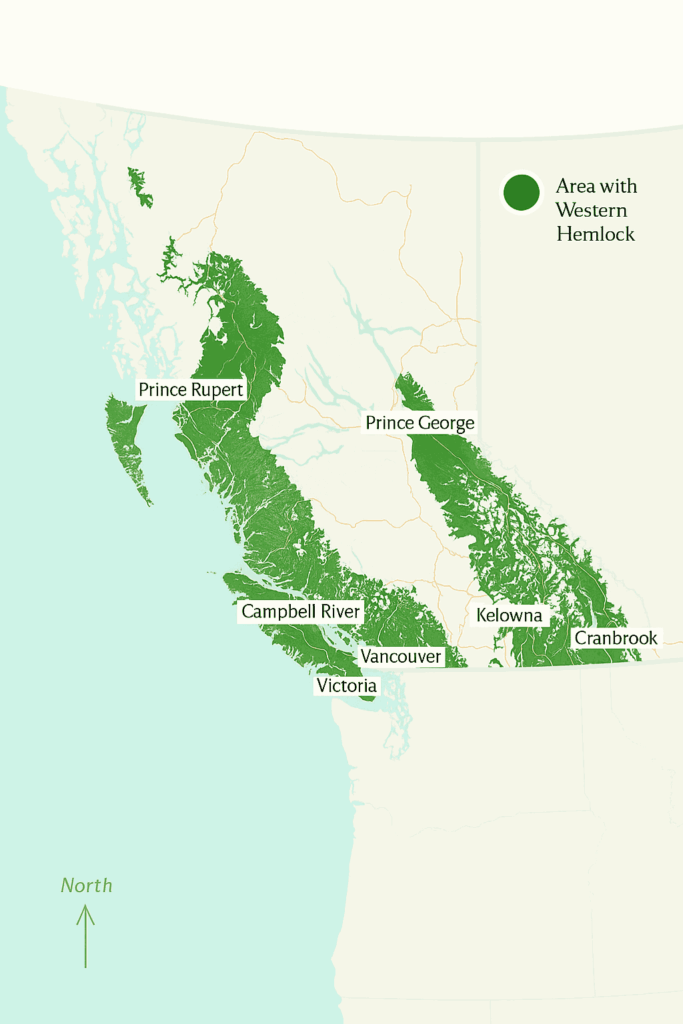

A coniferous tree of the Pinaceae family and genus Tsuga, it is one of several hemlock species that grow in North America and Asia. Also known as Pacific Hemlock, or West Coast Hemlock, this is a tree that is particularly dominant in the moist cool forests of British Columbia, Washington and Oregon.

Figure 1. Mature Western Hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla) showing its tall, pyramidal crown and characteristic drooping branch tips.

Western Hemlock is native to the Pacific Northwest, and extends along the coast in southern Alaska, coastal British Columbia, Washington, Oregon and northern California into the redwoods.

It is not only the most abundant tree within this range, but it is also a pillar of the forest ecosystem, both ecologically and economically to humans.

Western Hemlock also exhibits a remarkable capacity to survive in shady environments in the urban environment like Seattle, making it the most shade-tolerant conifer in the Pacific Northwest.

How to Identify Western Hemlock Trees

It is relatively easy to identify a Western Hemlock once its characteristic features are known. Its leaves are flat, soft needles that range in length between a quarter and three-quarters of an inch.

These needles appear to be in a flattened spray due to their twisted petioles, yet they coil around the twig. The undersides of the needles are marked by two conspicuous white bands, which are a sure identification mark.

Figure 2. Close-up of Western Hemlock needles showing their flat shape, rounded tips, and distinct white stomatal bands on the undersides.

Another characteristic is the branches of Western Hemlock. They are of a hanging nature, with the ends of both the side branches and of the main shoot turning downwards.

This downward slanting shape endows the tree with a graceful, rather feathery effect in comparison to the stiffer shapes of spruces and firs. Young trees have a thin and scaly bark, which is reddish-brown in color but darkens when the trees age and develop narrow furrows.

Among the most well-known identification marks is the profile of the tree. The crown starts as a narrow pyramid during youth, but as it grows older, it becomes broader and irregular. The uppermost shoot, or leader, sags conspicuously, in contrast to most other tall conifers in the region. All these features can be noticed annually, which makes them dependable even in the winter.

Figure 3. A cone or cluster of Western Hemlock trees is small and oval-shaped and has the dimensions of one inch, as well as hanging down branch tips.

Key Characteristics of Western Hemlock

Western Hemlock is one of the largest trees in the areas where it grows naturally. Mature trees grow to a height of 125-200 ft; and old-growth to well over 250 ft and 9 ft in diameter. This qualifies it as one of the heaviest of the shrubs in the Pacific Northwest, second only to Douglas-fir, western red cedar, and Sitka spruce.

- Leaves are soft and rounded as opposed to the prickly leaves of fir or spruce. This tenderness additionally gives it a feathery appearance.

The shape of the crown changes with time, being narrowly cone-shaped in juveniles, and broad and irregular in older trees (particularly of open-grown trees).

Figure 4. Western Hemlock branch with small oval cones hanging from the tips, a key feature for species identification.

The root system of the western hemlock is shallow and spreading. Although this enables the tree to take advantage of surface nutrients in organic-rich soils, it predisposes the tree to the effects of windthrow within a vicious environment.

This notwithstanding, it has the advantage of growing in dense shade compared to other species in forest succession. Actually, Western Hemlock can grow with up to 95% shading, so seedlings can stay in the understory until canopy openings provide the sunshine needed to grow quickly.

Western Hemlock Cone Structure and Reproduction

Western Hemlock has small and characteristic reproductive structures. They are oval in shape, three-quarters to an inch in length. Western Hemlock cones are left dangling at the end of a branch as opposed to the upright fir cone. Hanging orientation and the fact that they are relatively small are important diagnostic features.

Figure 5. Close-up of a Western Hemlock cone hanging from a branch, showing its small oval shape and overlapping scales.

Each cone contains a large quantity of winged seeds dispersed principally by wind in late summer and early fall.

- Cones normally begin to be produced when the tree is 20 to 30 years old, although in favourable conditions, others can begin to reproduce earlier.

The cones take only one growing season to mature and last throughout the winter, another helpful clue to identification. Since cones are prolific, they are usually the most dependable feature to identify species in mixed coniferous forests.

Where Western Hemlock Trees Thrive Naturally

Western Hemlock has a wide native range that is ecologically diverse. The species extends east across the temperate rainforests of coastal Alaska, down British Columbia, western Washington and Oregon and into the coastal ranges of northern California. In Washington it is especially common west of the Cascade crest and is the dominant form of lowland and mid-elevation forests.

Figure 6. Distribution map showing the natural range of Western Hemlock across coastal and interior British Columbia.

Western Hemlock reaches its lowest growth from sea level to an elevation of 7000 feet south of its range. It prefers wet well-drained soils that may include a lot of organic matter. The species is the most prevalent in valley bottoms, downslope, and coastal environments where fog and rainfall keep the environment very humid.

Western Hemlock best adapts to cool wet winters and cool wet summers. This is what makes the temperate rainforest climate in the Pacific Northwest a good location. In USDA zone 9a of Seattle, the species has an urban ecological niche, contributing to the ecological and aesthetic diversity of urban parks, trails and residential neighborhoods.

Growth Patterns and Development Rates

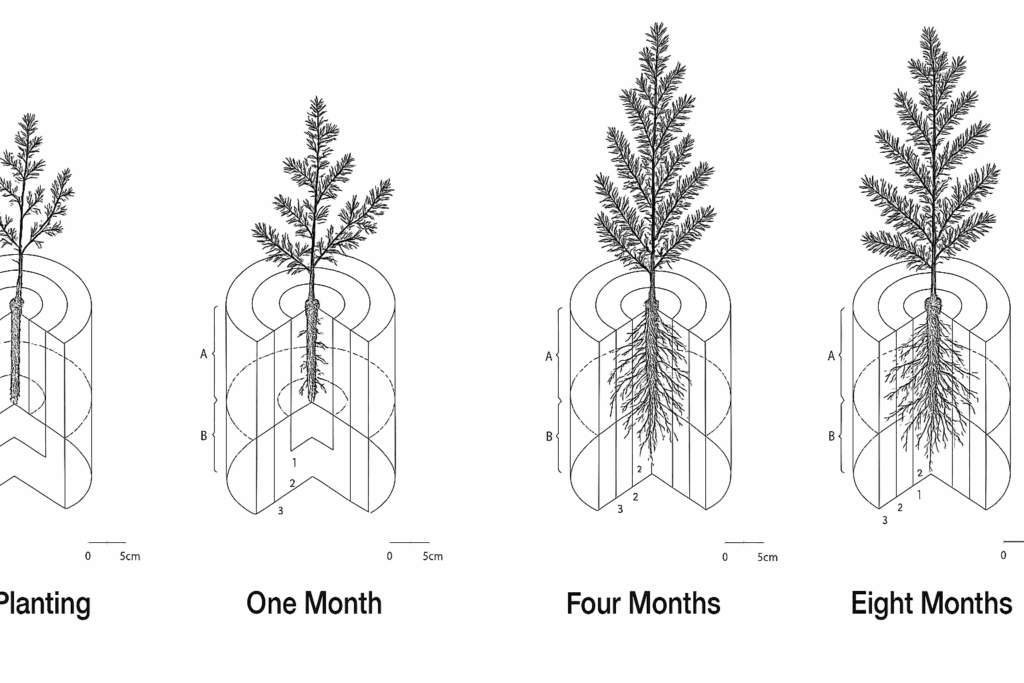

The Western Hemlock grows at a variable rate based on conditions. In ideal situations for a forest, with an abundance of moisture and high nutrient-rich soil, it will grow 12-18 inches per year. However, when in its juvenile stage, it will grow slowly and it may take many years before it increases its light acceleration.

Figure 7. Illustration of Western Hemlock seedling shoot and root development from planting to eight months, showing progressive root expansion and growth.

The tree achieves maturity when it starts producing cones, which usually occurs after 20-30 years old. Full reproductive potential and monopoly of canopy position may require much more time, particularly in competitive mixed forests. Old-growth specimens are frequently several hundred years old, and some have lived over 800 years.

There is an excellent impact of environmental factors on development. Trees in full sunlight on well-moistened soils can grow very fast in height, and those in shaded understories wait patiently until succession processes permit upward growth.

Its high shade tolerance causes Western Hemlock to be an essential climax species, and it becomes dominant in forests following pioneer trees such as Douglas-fir.

Comparing Western Hemlock to Related Species

Western Hemlock can be easily confused with the eastern one, Tsuga canadensis, but there are evident differences. In eastern hemlock, the most abundant tree in forests of the Appalachian region, the needles are shorter, the cones small, but in western hemlock, they are much longer and even an inch long. Most western species are also taller on average, and several large specimens are found in the Pacific Northwest.

Figure 8. Comparison of western hemlock, coastal Douglas-fir, whistler spruce and mountain hemlock foliage which shows the needle shape, as well as pattern differences among the species (Credits: hikeinwhistler.com).

The most similar species with which it is said to have been confused is with Mountain Hemlock (Tsuga mertensiana), which occurs at higher altitudes. Mountain Hemlock has needles more radially arranged around the twig, and bluish-green in colour and larger cones. Mountain Hemlock thrives in a sub-alpine environment and often flourishes in snowy environments, and Western Hemlock thrives in a coastal lowland and mid-elevation woods.

Where their ranges overlap, habitat preferences are discriminating. In the shady coastal forests, Western Hemlock is by far the prevalent; on the other hand Mountain Hemlock occurs on high, wind-exposed ridges and slopes. The two species in common show the ecological plasticity of the Tsuga genus in the Pacific Northwest.

Why Western Hemlock Became Washington’s State Tree

Western Hemlock was declared the official state tree of Washington in 1947 as a symbol of the prevalence and importance of the tree to the economy and identity of the region. Other trees such as Douglas-fir, were also considered during the time, but Western Hemlock was successful because it was seen as the tree that best relates to the evergreen forests covering the state.

Figure 9. Massive Western Hemlock trunk with deeply furrowed bark and wide basal fluting, typical of mature old-growth specimens in Pacific Northwest forests.

Western Hemlock had been of a longer standing value to the Lumber and paper industries. Its wood was not as strong as Douglas-fir but it proved to be very versatile in construction, plywood and of utmost importance, pulp to make paper. The tree was also significant culturally to Indigenous people, who used its bark, roots, and branches in dyes, medicine, and around the house.

The Western Hemlock has also become the sign of the natural affluence and ecological richness of Washington. It is not in danger, yet the existential impact of climate change, pests, and loss of habitat are all cited as influences that may cause its long-term stability, and thus, protectionism is justifiable.

Essential Western Hemlock Facts and Uses

Western Hemlock is a species with a very long life, which lives to 400-800 years in natural habitats. The wood is relatively light but strong and can be used in many ways, including construction framing, millwork, and joinery. It is beneficial in the manufacture of pulp and paper, and large-scale harvesting has been the basis of regional economies in the twentieth century.

Figure 10. Western Hemlock wood is crafted into furniture, valued for its light colour, fine grain, and reliable structural properties in construction and interior design.

Ecologically, Western Hemlock serves as food and shelter to the wildlife. Birds and deer, elk and small mammals feed on the seed and browse its leaves and bark. The dense canopy, combined with the evergreen litter that creates the brown, acidic forest soil that is commonplace in central New South Wales for the species of the understory. Being of a climax species, forestry is a key element in the succession of the forest population, plays a role in maintaining ecosystem stability and stores carbon.

Figure 11. Mature larva feeding on Western Hemlock needles, a common defoliator affecting forest health and regeneration.

Western Hemlock was used in large quantities by Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest. They were sometimes fermented into teas to be prescribed medicinally, and the tannin contained in the bark was used to tame hides. These traditional practices signify that there is a close linkage between people and the forests of the region.

Frequently Asked Questions About Western Hemlock Trees

How tall is a Western Hemlock?

Western Hemlock generally grows between 125 and 200 feet tall, with rare old-growth specimens surpassing 250 feet.

How long do Western Hemlock trees live?

In natural forests, Western Hemlock can live 400 to 800 years, and in some cases over 1,000 years.

Is the Western Hemlock tree poisonous?

No. Western Hemlock is not poisonous. It should not be confused with poison hemlock (Conium maculatum), which is an unrelated and toxic herbaceous plant.

What eats Western Hemlock?

A variety of wildlife interacts with Western Hemlock. Deer, elk, and porcupines browse its foliage and bark, while birds and small mammals consume its seeds.

What is Western Hemlock wood used for?

The wood is used for construction, plywood, millwork, furniture, and especially for pulp and paper production. Its versatility makes it an important commercial species.